The Natural Virtuoso As High School Hero

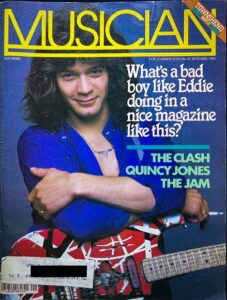

The article below was originally published in the September 1982 Musician magazine. It was written by J.D. Considine.

Eddie Van Halen transcends the hyperbole of arena rock with a truly electric style of guitar playing. often borrowed and rarely duplicated JD Considine conducts a rare lengthy interview with the crown prince of 6-string flash 'n' skill as well as brother Alex and superfop David Lee Roth

by J.D. Considine

No, you haven’t wandered into an issue of Circus by mistake. Sure, Van Halen is exactly the kind of a band your fourteen-year-old kid brother thinks is the greatest thing since zit cream or the girls’ locker room scene from Porky’s, but so what? Maybe the kid is a little smarter than you think he is. If you go only by what you hear on the car radio, something like “(Oh) Pretty Woman” or ‘You Really Got Me,” an assault on the Kinks classic that rocketed the band to stardom in 1978, it’s easy to simply assume that these are just four more metalloid morons out to make a quick buck. But if you really sit down and listen to what the band is doing, you may think twice about dismissing them so hastily.

The guitar playing, in particular, almost defies description. Instead of the usual flash-and-dazzle effects most guitarists have been repeating since they were first laid down by Clapton, Beck Page, Hendrix, and Blackmore, Edward Van Halen pulls all sorts of crazy stunts with harmonics, his tremolo bar and a host of makeshift techniques that are hard to believe even after you’ve seen how they are done. Perhaps the most amazing of these is a two-handed version of the hammer-on and pull-off—a technique in which instead of plucking the note with a pick, the first note is sounded by hitting the string very hard at the fret, then plucking the string with that finger to sound a second, lower note—that on “Eruption” resulted in shimmering arpeggiated figures that sounded more like a Bach harpsichord than rock guitar.

Nor are all these tricks saved for the solos. Van Halen crams guitar moans, growls, shrieks and chatter into almost every available nook and cranny on the band’s five albums. Yet the records never end up sounding like guitar solos, largely because this isn’t a one-man group—it’s a quartet in every sense of the word. On a strictly instrumental level, that means as Edward Van Halen takes his guitar into the stratosphere, his brother Alex is right there, keeping pace on the drums while bassist Michael Anthony draws the bottom line; on an aesthetic level, it balances the music’s sophisticated energy with a perspective best summarized by David Lee Roth’s deadpanned, “Have you seen junior’s grades?”

It’s that combination of musical audacity and juvenile delinquent sensibility that has made Van Halen what it is today: a major concert attraction, an FM rock staple, and a convenient target for critical abuse. Granted, that last is something of a two-way street—David Lee Roth made few friends in the press when he postulated that the reason more critics liked Elvis Costello than Van Halen was “because most critics look like Elvis Costello”—but it’s also more the result of stylistic snobbery than objective analysis.

When Van Halen burst out of the Hollywood club scene in 1978, they were the biggest, brashest, most over-the-top heavy rock band around. Their subsequent success has only amplified those tendencies. Describing the band’s views about their Van Halen roadshow, David Lee Roth asks, “Remember when you were in school, and the whole thing revolved around who had the biggest tires in back, who had the loudest stereo? Well, we never got past that phase.” They sure haven’t. On the band’s last two tours, the stage was divided between a wall of 12-inch guitar speakers and a wall of 12- and 18-inch bass speakers, with a drum kit resembling the contents of a small percussion store mounted in the middle. Looking down the barrel of all this acoustic firepower, you begin to wonder what they need a P.A. system for, but without it how could you follow Roth’s between-songs patter? Clutching a mostly empty fifth of Jack Daniels during a concert in Philadelphia last year, Roth cheerfully explained to the fans, “Of course I drink on the job. That’s how I got the job.”

Nonetheless, the most ear-grabbing moments invariably belong to Edward Van Halen. As much as Roth’s banter and the physical excess of the stage gear testify to the extravagances of the rock ‘n’ roll life, it’s the free-flowing energy and imagination of Edward’s playing that captures the music’s spirit. His solos are flashy, unpredictable, and totally idiomatic, adhering to a logic that seems to apply solely to electric guitar and possessed of an almost palpable dynamism.

Because the members of Van Halen apply their talent to a fairly basic version of rock ’n’ roll, a lot of musicians figure they must be as cretinous as every other three-chord wonder. “When we were going to school studying to learn the basics,” recalls Alex Van Halen, “they used to call us musical prostitutes because we were playing songs that had no fancy chord changes but only the basic l-IV-V. They used the premise that, ‘because my thing has nineteen chord changes and two-meter changes, my thing is music, and yours stinks.’

“Well, I say stick it. For all intents and purposes, it’s much more difficult to write a song that’s memorable, that people can sing along with, using only the basic l-IV-V as opposed to applying your musical skills to bend things out of shape.”

Of course, there’s a certain irony to Alex Van Halen having to defend his music on the grounds of musicality, for both he and his brother, as well as Michael Anthony, come from house¬holds where music brought home the bacon. Jan Van Halen was a professional clarinetist and saxophonist who started his sons on piano lessons at age six, while both of Anthony’s parents were professional musicians and he started playing trumpet in the second grade. (David Lee Roth, on the other hand, comes from a long line of doctors and other socially respectable types, proving that there’s one in every family.)

Edward Van Halen seems to be a natural in the truest sense of the word. Alex reports that “when Ed first picked up the guitar, he could play better than the guys at ’hat time who had been playing for years. My dad, who’s been a professional musician all his life, says Eddie plays like Charlie Parker, only he doesn’t need the drugs.”

His peers are equally effusive. Carlos Santana has called his playing “brilliant.” Frank Zappa recently thanked him “for reinventing the guitar.” Perhaps the most incisive compliment came from Andy Summers of the Police, who said. He is a natural virtuoso. What impresses me is his passion, his spirit, and his musicality. Really, I think he is the greatest rock guitarist since Hendrix.”

Talent runs in the Van Halen family, though, and Edward didn’t get it all. “Alex is better technically at music than the rest of us combined,” insists Roth. “I remember that before we all got thrown out of school for the last time, Alex redid all of the music for West Side Story and arranged it for a fifteen-piece jazz-rock ensemble. And he had to go around to each instrumentalist and show them how to play their part, because nobody could figure it out. He was doing stuff in 11/8 time…. Plus he’s got near-perfect pitch. You can play him a song on the radio, and he’ll tell you what key it’s in.”

The idea is to play as a unit, and that holds true as much for recording as playing live. “Most of the time, what a band will do is get a click track and set the drum part down on tape with the bass and maybe rhythm guitar,” says Alex Van Halen, “and then they build it from there. We play together, and if by the second or third take the song is not to our satisfaction, then we move on to a different one. Because our opinion is if you can’t get it right the first or second time, you shouldn’t even be there. What we do is rehearse the material to the point where it’s ready to be played onstage, ready anywhere, and then go up to Ted (Templeman, the producer) and Don (Landee, the engineer) to put it on vinyl.”

Even then, the studio performances tend to be pretty spontaneous. “We know the basic structure of the song, what we’re going to do,” says Edward Van Halen, “like how many bars will go here, how many choruses we’re going to do, whether we’re going to fade out. But when it comes to solos, I never work ’em out. I never even know where I’m going to start. The fingers just kinda go.”

Roth laughs, and confides, “It comes so easily. Of course, there are probably people out there in magazineland right now saying, ‘That’s because it’s crap,’ and it may well be. But it’s my crap. It’s fast. It comes easy, and it’s enjoyable. Otherwise, it would be just like another job.”

MUSICIAN: Let’s start at the beginning.

VAN HALEN: Alex and I, we were both born in Holland, in Amsterdam. My father was a musician, touring around, and so of course both his sons would be musicians. He played everything, jazz—big band or whatever—and classical. He met my mom in Indonesia, and he used to play in classical concert-type things. Well, he got us to practice piano since we were about six years old. When I was eight years old and Alex was nine or ten, my mom decided to move to the land of opportunity. So we moved over here and quickly lost interest in sitting down and going like this (adopts stiff-armed, ramrod-backed posture of classical piano student).

MUSICIAN: Did it take long to get indoctrinated to rock ‘n’ roll?

VAN HALEN: Not very long at all. We were kind of sheltered from it, we didn’t hear very much of it when we were in Holland, even though right across the English Channel was where it was all coming from. It was definitely, “Turn that stuff down!” same as any other kid. Beaten to play the piano, you know….

But we persevered, and I got a paper route so I could pay for my $41.25 St. George drum kit, and while I was out throwing the papers, my brother was playing my drums. He got better, so I said, “Okay, you can keep the damn drums.”

At the same time, my parents thought they could expand on Al, so while I was out throwing papers, they made him take flamenco guitar lessons. So I started plinking around on his guitar after he took my drums, and it just kinda went from there. And if you look at both of us now, it’s lucky that we both changed because he’s twice the size of me. He doesn’t look like a guitarist.

MUSICIAN: Did you keep on playing piano through all this?

VAN HALEN: Off and on. I actually started playing guitar when I was about twelve, and when I was sixteen I totally dumped piano. Up until then I was still forced to practice, (affects gruff, authoritarian voice) “Okay, if you’re going to play guitar, you’re going to have to play piano and make up for it.” I remember if I came home too late on Friday or Saturday night, my mom would lock my guitar in the closet for a week, things like that. Torture!

MUSICIAN: So then it was out of the conservatory, into the garage?

VAN HALEN: Yeah. It was basically just Alex and me. To tell the truth, it’s been Alex and me since then, with whoever. It started out with just the two of us playing, and then we said, “Hey, it sounds kinda thin. We need a bass player.” (laughs) So we went through a handful of bass players. Then I got sick of singing, and we got Dave in the band.

And then we started playing clubs, like Gazzarri’s and stuff. The old bass player we had used to smoke too much pot and hash. We had a repertoire of about 300 songs that you had to remember, and he’d be so high, he’d be playing a different song. So we got rid of him and got Mike. And that’s the way the band is now, it’s been about eight years—74-75 was when Van Halen was formed, and it was Dave’s idea to use Van Halen for the band name. I wanted to call it RatSalade (laughs wickedly). I was into Black Sabbath then….

MUSICIAN: That’s funny that it would have been Dave’s idea, because he’s the one most kids recognize first.

VAN HALEN: They think he is Van Halen, like Van Morrison. They think he’s Van. We played Gazzarri’s for maybe three years, and if it was a good weekend Bill Gazzarri would slip us an extra twenty bucks on the sly, and he’d always hand it to Dave. For three years on end he went, “Here, Van. It was a great weekend.”

MUSICIAN: I understand that in your club days you did a lot of songs most folks wouldn’t associate with Van Halen.

VAN HALEN: In clubs, we used to do “Get Down Tonight,” and all that stuff. We’d hum the horn parts, and Dave would sing on top of that. It sounded funny, it sounded very funny, but at least we got hired.

MUSICIAN: Was that a factor in your “anything goes” approach?

VAN HALEN: Definitely. ’Cause Dave has different taste in music than the rest of us—we all have different tastes. I think the only true rocker of the bunch is Al. He’s the only one who listens to AC/DC and all that kind of stuff. Dave will walk in with a disco tape and I’ll walk in with my progressive tapes and Mike walks in with his Disneyland stuff (laughs).

We’re all so different, I guess that’s what makes Van Halen so different. If we were all like Dave, we’d all be playing Dave Music. And even though I write the music, the final product is still all twisted and bent. For a one-guitar band, I think we do have a little variety, and I think that’s because of their input.

MUSICIAN: You can listen to a lot of guitarists and fairly easily tell who they’ve taken from, but your influences really seem to have gone through the Cuisinart.

VAN HALEN: I sometimes wonder myself when it was that I turned the corner and went my own way in playing, because the last thing I remember was playing “Crossroads” and being Eric Clapton. I used to play all that stuff note-for-note, and play exactly like him. I don’t know where all of a sudden I just changed.

MUSICIAN: Clapton was a big influence?

VAN HALEN: My only. He was the only one I ever copied. I didn’t care too much for Jimmy Page or Hendrix or anyone else. Beck I didn’t even know about until Blow By Blow came out (laughs).

MUSICIAN: What was it about Clapton?

VAN HALEN: Oh, just a feeling. Clapton just had something that I liked, it sounded smooth and warm-toned, as opposed to Hendrix who was always eeyarrrowwngk’. Even though I probably do like Hendrix more than Clapton now. All the rest of ’em I’ve heard and stuff, but never really sat down to cop a lick from ’em or anything. Alan Holdsworth, he’s so damned good I can’t cop anything—I can’t understand what he’s doing. I’ve gotta do this (does two-hand things) whereas he’ll do it with one hand. Or it sounds like it sometimes. Beck, Page, Hendrix, Townshend—I love Townshend’s rhythm playing. I love the sound he gets for chords.

MUSICIAN: What sort of things do you listen to at home?

VAN HALEN: Progressive stuff, like Alan Holdsworth, stuff like that. Brand X. That’s about it. I don’t listen to much rock. I listen to a lot of Chopin, piano. Very little rock ’n’ roll.

MUSICIAN: To get back to what you were saying about getting bored by the same thing over and over again, one of the most common complaints about rock ‘n’ roll from real sophisticated players is that it’s all in the key of E. So I’m curious how you feel about rock’s musical limits, because while some of your stuff seems to have moved beyond that, on the other hand you’re still….

VAN HALEN:… in it. That’s what’s so challenging about rock ’n’ roll, that pressure of “You’re stuck!” Trying to get out, but you’re still in it. Like what you said about playing in the key of E. A lot of guitarists hate rock ’n’ roll because you’re stuck with that. You’re not. You can play any way you want, as long as you’re playing chromatic or whatever and you end up on a note that kind of fits the key. And along with the harmonics and the weird noises, you’re not limited. I mean, you always have to goto some key, I don’t care what type of music you’re playing.

MUSICIAN: In the past couple weeks, I’ve listened to the new Scorpions album and found myself saying, “Gee, that guy sounds a lot like Eddie Van Halen.” Then I put on the new Rainbow album, and there’s a solo that could have been you.

VAN HALEN: (chuckles) Blackmore hates me.

MUSICIAN: And then there was Randy Rhoads….

VAN HALEN: Oh, yeah. He did me to the bone, bless his soul.

MUSICIAN: And the guy they got to replace him does a lot of the same licks, too. So obviously, you’re reaching somebody.

VAN HALEN: Yeah (laughs embarrassedly). Yeah, I guess you’re right. I met Frank Zappa the other day, and the first thing he said to me is, “Thank you for reinventing the electric guitar.” Which was a hell of a compliment coming from him, because I love Zappa.

MUSICIAN: But I take it you really don’t think you’ve “reinvented the electric guitar”?

VAN HALEN: I don’t know. I just do what I do, and I really don’t consider it inventing, or doing anything but what I do. Just because everybody is doing me now… is nice, but maybe two or three years down the line I’ll be doing me in a different way.

MUSICIAN: Turning that around, do you think you’d still be playing the same way if you were back in the clubs?

VAN HALEN: I think so I was playing this way when we were playing clubs, and I remember what I used to do, too. Because nobody over used to do this before (he picks up his guitar and does some fast, two-hands-on-the-fretboard playing). After I somehow stumbled on it, when I would do a guitar solo and do that stuff, I’d turn around because I didn’t want anyone to see how I was doing it (laughs). I’m going, “Not until we get signed, I don’t want anyone to know!” (laughs uproariously)

Actually, it was my brother who told me, “Turn around when you do it. These bastards are going to rip you off blind.” And he was right! There was a band called Angel who tried to rip us off, and luckily we just got signed. They tried to go in and do “You Really Got Me.”

See, I was star-struck. You know, “Hey, our rock band just got signed!” So I played this guy from Angel our album a month before it was going to be released, and a week later Ted Templeman calls me and he goes, “Did you play that tape for anybody, you asshole?” I’m going, “Yeah, wasn’t I supposed to?” “I told you—Damn! I never should have given you a copy!” And I’m going, “Why, what happened?” Well, he had heard from the tour manager with Aerosmith that a band called Angel was in the studio trying to rush-release “You Really Got Me” before we could.

So I’m glad I turned around for a year or two.

MUSICIAN: What about your guitars? I understand that some of them you built yourself.

VAN HALEN: Yeah, yeah…I’ve still got the original guitar I built. You want to see it? (He goes off and comes back with a red. Stratocaster-styled guitar adorned with black and white stripes and bicycle reflectors on the back.) It’s the one I record with and play onstage with, and it’s the biggest piece of junk you’ve ever seen in your life. That’s my main baby.

MUSICIAN: What is it—aside from the decorations—that makes this guitar so special?

VAN HALEN: I think it’s just that it cost me $200, and I don’t believe in spending a lot of money. The most important thing is this pickup. (He points to a humbucking pickup in the bridge position, and then indicates a Fender-style soapbar pickup that is rather pointedly not wired in.) That’s just something to fill up the holes.

This is the first one, it’s on the first album cover. I originally had a Strat, but I couldn’t handle the way it sounded because I’d play so loud I’d get such a hum, such a buzz. And I’m going, “Why is it doing this?” Then someone told me it’s single-coil pickups, and I discovered what single-coil pickups were as opposed to humbucking. So I carved out part of the wood and slapped a humbucking in the Strat. But no matter what I did, always right here on the E (plays octave fret on the low E string) I got a vibration. I started looking around for better wood. And then I ran into Charvel guitars, and they had a junk body laying there so I said, I’ll give you $50 for it, and this thing came alive.

MUSICIAN: So why, with all the guitars since, do you stick with this one?

VAN HALEN: Every time I get a different guitar, whether it be playing in the basement, onstage live or in the studio, we’ll be playing and someone will say, “Are you using a different amp, Ed?” And I’ll say, “No, it’s a different guitar.” They’ll say, “Use your other one. It sounds better” (laughs). It usually takes a few songs before someone says anything.

I’ll tell you how this happened. I told you I used to have a Fender Strat. When I ripped the guts out—I didn’t know how to put it back! I swear to God! The three knobs and the switch …I’m going, “Goddamn, I don’t know what the hell’s going on.” So I just took everything out and took the two cords that went from here to there (traces the path from the pickup to the volume knob) and the two from there (indicating the jack) and switched them around until I heard something, and clamped it down. That’s the way it is, and it works great.

That’s how I stumbled onto the one volume knob. All you see kids using now is one volume knob and one pickup. Little do they know it’s out of ignorance.

MUSICIAN: The one thing that’s most intrigued me about your sound is that for all the weird things you do as a player, your sound always seems pretty straight.

VAN HALEN: Yeah. I have a whole effects rack that my roadie built for me and was proud of when he was done, but I never use it. ‘Cause it never works, or I hit buttons and I’m going, “Eh, screw it! I’d rather make noise on the guitar.” Instead of using effects.

I’ll use an occasional echo—it’s kind of a slow repeat to fill out things, make it a little more majestic or whatever. But I’m not into all these little things that make your guitar sound not like a guitar.

MUSICIAN: What kind of amp do you use? I tried counting the speakers during one show and lost count somewhere around sixty-four….

VAN HALEN: Live I always use six old 100-watt Marshalls, each through four speakers. No, eight. Through all my bottom cabinets I use one head, ’cause I have six cabinets supplied, and one head for each cabinet. They’re actually double cabinets, eight speakers in one, but I just had ’em built that way because it’s easier to move ’em around. They’re still divided, they’re still separate cabinets.

MUSICIAN: Do you use the same setup in the studio?

VAN HALEN: It depends on how loud I feel like playing. When you’re close-miking one speaker it doesn’t matter how many amps you’re using. It really doesn’t.

Oh, we use one room mike to mix in there with it, but it’s so simple. I mean, Ted Templeman, our producer, got in trouble for saying this. He did an intervew for BAM magazine, and they asked him, “How do you do the Doobie Brothers? How do you do Van Halen?” And he goes, “Well, with Van Halen it’s so goddamn simple—all I do is throw mikes up there, they play it and we’ve got it. With the Doobie Brothers, I’ve got to do this and that and this….” And the Doobie Brothers got all pissed off at him.

MUSICIAN: How much overdubbing do you like to do?

VAN HALEN: None, actually. I hate doing it. On the new record, I only overdubbed a few things. No, actually a lot. Let me think: “Where Have All The Good Times Gone,” nothing; “Little Guitars,” I overdubbed the slide in the middle; “Hang ‘Em High,” nothing; “Secrets,” just the solo—I used a 12-string on “Secrets,” one of those double-necked Gibson jobs; “Intruder,” nothing; “Pretty Woman,” nothing; “Big Bad Bill,” nothing; “Dancing In The Street,” I doubled the synthesizer with the guitar and overdubbed the solo; “Cathedral” was one guitar; “Happy Trails,” a lot of overdubs (laughs); “Full Bug,” nothing. Well, Dave did a harmonica solo.

I hate to overdub. It’s just that I can’t stand to wear head-phones. I never wear headphones in the studio, I stand right next to Al and play. I prefer to do the solo on the basic track and if it needs it, overdub a rhythm guitar—even though I didn’t do that this time around. I don’t know, I feel like I’m in a glass bottle separated from the rest of the guys whenever I put headphones on.

MUSICIAN: It’s interesting that you stand next to Al. Is that what you listen Io onstage as well? What’s in your monitor?

VAN HALEN: All I have in there are drums and a little bit of Dave’s voice, and my voice. Mike I can never hear, whether it be in the studio or live, I never hear him.

MUSICIAN: Does that bother you at all?

VAN HALEN: No, not at all. I guess he more follows me than I follow him, and I’m more of a rhythmic player, so I need a lot of drums. And whenever Mike’s bass gets in there it garbles stuff up. The frequencies of the bass drums and stuff and of his bass don’t work right.

MUSICIAN: A lol of bands work with a bass-drums axis; some use a rhythm guitar-drums axis, but you guys seem to have an almost invisible axis.

VAN HALEN: Yeah, yeah, exactly. It’s like ESP sometimes. Even if my monitors don’t work right live and I’ll make a mistake, Al is right there with me, or vice versa.

MUSICIAN: I was kind of surprised at the down-to-earthiness of Diver Down, because the last record was really abstract.

VAN HALEN: I still don’t understand that. So many people tell me that. What is so abstract about it?

MUSICIAN: Abstract in the sense that the songs aren’t really verse-chorus-verse-chorus….

VAN HALEN: Well, our songs never really have been, have they?

MUSICIAN: Yeah, but you get that impression on the new one simply because you’re doing so many cover versions of old songs.

VAN HALEN: Yeah, you’re right. I guess the reason being those are other people’s songs. If you listen to our songs on the record, they’re just as wacko as those on the last one. They’re not structured that way. Our songs never are.

MUSICIAN: Even then, the stuff on Fair Warning went a little farther afield. Like on “Dirty Movies,” where Michael goes into the funky bass riff—you don’t get that on the originals on this album.

VAN HALEN: Well, that’s a toughie, because “Secrets” on the new album, I wrote that last year. I wanted it on Fair Warning, and everyone’s going, “Aaaah, pffft!” They didn’t like it. ‘Cause I do write all the music for the band. They kind of pick out of everything that I have, and they say what they like and don’t like. And all of a sudden, just because…. See, Ted Templeman never heard it, and when Ted heard it, he liked it, and all of a sudden they liked it too. (laughs) No, don’t print that.

I find myself, when I write, I always go in lumps, “Hey, these five songs all kinda sound the same.” So we kinda spread ’em out; we use one next album, and one now. I mean, they’re not ‘identical, but you can tell I wrote ’em at the same time, around the same period. It’s impossible for me to forget what I’ve done completely, so I’ll never write it again. Because I’ve done that before.

MUSICIAN: After talking about some of the things you do, and after listening to your versions of the album material, I can’t help but wonder why you don’t do a solo album.

VAN HALEN: Each album already is, actually. I can do basically what I want ’cause I write all the music anyway, so it already is kind of a solo thing. Even though we all get credit, but what the hell. That’s a deal we made in the beginning.

MUSICIAN: To get back to the album, how did you do the acoustic guitar intro to “Little Guitars”? It really sounds like bona fide Spanish guitar there.

VAN HALEN: Aw, yeah, I did a great cheat on that one. Everyone thinks I overdubbed on that. I’ll show you what I did. (He picks up a guitar and picks a single-note trill on the high E string, using his left hand to play the melody on the A and D strings using hammer-ons and pull-offs.) I did it like that, pull-offs and hammering.

That’s all I did, and people are going, “Naw, c’mon, you overdubbed that.” Then I show them how I did it.

Classical guitarists can do that, but they singer-pick. I can’t finger-pick. No, I definitely cheated. I’m good at that, I’m good at cheating. If there’s a sound in my head and I want’ it, I’ll find a way to do it. Whether I know how to do it by the book or not, I’ll figure out some way. You can ask my wife I bought a couple of Montoya records, and I’m going, “God. I actually started trying to finger-pick, and I’m going, “Screw this, it’s too hard.”

Even Ted was blown away. I had a little machine like this and I put it on tape, and I said, “Ted, what do you think?’ He’s going, “That’s not you, I know you can’t finger-pick.” I said, “Here, gimme a guitar, I did it like this.” They all started laughing.

I just do everything the way I want to do it. Period. ’Cause that’s the way it’s easiest for me. Why make it hard on yourself? I mean, who is the God of Guitars who says it has to be held this way or that way? If in the end result you get the same noises and the same whatever, do it however you have to do it. Instead of following the book, I just stumble on things. It’s not like I’m creating anything—just through mistakes I come up with things, I guess. And then I like it.

Musician: Much of what you play seems classically derived. Like the guitar, stuff reminds me of Bach harmony studies.

Van Halen: I love classical progressions, like Bach, that kinda stuff, so I guess that’s what comes out. Just ’cause that’: what I want to hear. I definitely don’t now what I’m doing, if that’s what you’re getting to. (laughs) It’s by ear. I always tend to lean towards those types of progressions because that’s what I like, I guess. The sound, the mood it sets. I like it.

Musician: What about the jazzy chords you did on “Big Bad Bill”?

Van Halen: Those I read. You know, just…. I couldn’t play that song right now if you held a gun to my head, (grabs guitar and demonstrates) Something like that. It was so quick moving I couldn’t remember it….

It looked so neat, though, I wish I had a picture of it ’cause there was my father and me and Mike, and we’re all sitting down with sheet music in front of us in the studio. It looked like an old 40s thing, you know? I wish I had a picture of that.

Musician: How do you prepare to record? I assume you rehearse the songs first.

Van Halen: Oh, yeah. We know the basic structure of the song, what we’re going to do. Like how many bars will go here, how many choruses we’re going to do, whether we’re going to fade out. But when it comes to solos, I never work ’em out. I think there’s only been one ever, and that was on “Push Comes To Shove,” ’cause I wanted it…I liked the solo, too. It doesn’t sound worked out, even though it is.

Musician: Are the fills done off the top of your head?

Van Halen: Oh, yeah. They’re done playing live, except for Fair Warning. Fair Warning I did most overdubs, as opposed to every other album where I played live. Actually, I prefer it that way more, to play live, because I know the songs, and I’ll put in fills where they sound real, as opposed to on top of what’s already been done. If that makes sense.

Musician: Almost all rock guitar solos run the same way—they start out low and end high, and about two-thirds of the way through there’s all this fast stuff and then they go out on long notes. But your solos….

Van Halen:…are just everywhere. I guess maybe ’cause I don’t structure ’em.

Musician: I take it you’re fairly unconscious of that sort of thing?

Van Halen: Uh huh. I’m unconscious of a lot of things (laughs).

Musician: The reason I ask is that a lot of rock playing is so blunt, but yours is pretty well articulated.

Van Halen: I like doing that, like muffling with the palm of my hand, for dynamics. As opposed to using a volume pedal or stuff like that.

Musician: With all the things you do to your strings, are you ever worried about breaking one onstage?

Van Halen: If I break a string, Dave will just talk a little longer and I’ll change it real quick. Dave’s very good at talking.

Musician: I know. He gave me a demonstration last night.

Van Halen: Oh, you did an interview with him? You actually listened to him? What did he say?

Musician: He was explaining Van Halen in terms of Bauhaus architecture.

Van Halen: (laughing) Hoo-kay!