Pete Townshend (The Who) 1996

A rare interview with Pete Townshend

The interview is conducted by Steve Harris. To learn more about Steve please check out our podcast-only interview with him, which is out now.

In the interview, Townshend talks about:

- His non-defined image of himself

- His ability to write story-oriented albums

- Why it’s very hard to write songs

- His plan to no longer make records

- Why he is releasing a compilation album

- The notion that he hates the Japanese

- Developing Quadrophenia for a concert theater piece

- Which album he thinks is The Who’s best

- The backstory of when The Who revived ‘Quadrophenia’ for Prince’s Trust Concert

- Remastering old Who albums

- Writing chamber plays

- The difficulty of working in movies

- His lack of enjoyment for music theater

- What connects music from the ’50s and animation

- What’s important to him now

- The remixing process of Quadrophenia

- The previous poor mastering process of Who records

- Finding a Jimi Hendrix master in his warehouse

- The unfinished rock opera “Lifehouse”

- The mods 30 years later

- What he found hypocritical playing Black music

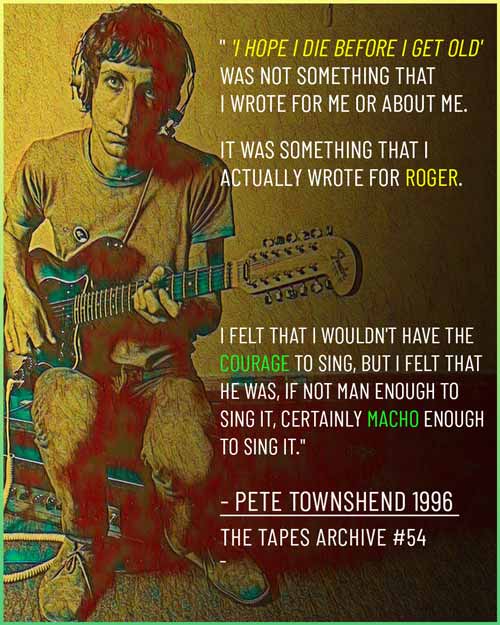

- How he feels now about his lyric “Hope I die before I get old”

- The songwriting that went into “My Generation”

- Kurt Cobain and the song “My Generation”

- Seeing Jimi Hendrix a couple of weeks before he died

In this episode, we have a founding member of The Who, Pete Townshend. At the time of this interview in 1996, Townshend was 51 years old and was promoting his greatest hits record. In the interview, Townshend talks about his plan to no longer make records, the remixing process of Quadrophenia, what’s now important to him, and finding a Jimi Hendrix master in his warehouse.

Pete Townshend Links:

Watch on Youtube

Pete Townshend's interview transcription:

Steve Harris: Peter, I’ve been given a list of questions by a Japanese journalist,

Pete Townshend: Right.

Steve Harris: from “Rockin’ On” magazine to pose to you. It’s gonna be a little bit awkward sometimes because sometimes the intention of the question does not come through exactly crystal clear. So if you can bear with me.

Pete Townshend: Okay,

what kind of responses do you want? Do you want them pithy or sound-bitey or… Are you gonna have to translate them?

Steve Harris: No, actually I’m just usually the guy who looks over the questions in Japanese, and then poses them, and then somebody else translates them at different time. So you can feel free to answer the questions in any way that makes you feel comfortable.

Pete Townshend: Okay.

Steve Harris: The first question is about the jacket photo from your compilation album. You look rather severe in that photograph, or what exactly was the intention behind that?

Pete Townshend: You know, I don’t think there was any intention. No, I didn’t have any intention anyway.

Steve Harris: Well, I guess for people who are in the non-English speaking world, a photo says certain things or has certain connotations that it might not have elsewhere. Maybe that’s why he asked this particular question.

Pete Townshend: It’s interesting ’cause I don’t have a very well-defined image of myself. When I look in the mirror, I’m surprised by myself. Now, that’s not just because I’m getting older. I mean, I’ve always felt that, I’ve always, my image of myself is not the person that I see in the mirror or in photographs. When you come across artists that do have a very strong sense of themselves, they learn to use that. And it’s something that they can use to great advantage. You know, somebody like Bowie for example, and not just because Bowie is photogenic and attractive, but because he does have a very good sense of the way that he looks. And he uses it in a very chameleon-like way. Even I think somebody like Eric Clapton, who I think he’s very good at having his photo taken. For me, the thing is, is that when it comes to an album cover, if I’m being photographed, I’m very much in the hands of the photographer. And I think that photographer must’ve had a brief to get a headshot in which it wasn’t revealed that I was going bald, that had lots of blue in it to go with my blue eyes, which women tell me are my best feature. And maybe he said to me, “Smile.” And maybe I said, “I can’t because I don’t feel like smiling.” I don’t know, I can’t act. So if the photograph had been taken on a different day at a different time, I may have looked very, very different. I mean, I’m quite surprised sometimes when I see pictures of myself and I’m laughing, how light I look, how happy I look, like how much of a different person I look. And then, you know what happens is somebody will say to me, “Oh, you should laugh more often. “You look lovely when you laugh.” And I think, “Fuck you, take me as I am.” And it’s very difficult to laugh all the time. It’s one of life’s greatest arts, isn’t it, to be cheerful?

Steve Harris: It really feels like it comes very naturally to some people, though.

Pete Townshend: Well, I think those people are very special people.

Steve Harris: What you’re saying, I’m trying to kind of grasp what it is you’re getting at, but maybe you’re saying there’s a little bit of the actor in most musicians and they can kind of project their looks as they like, but in your case, you don’t really have that capability.

Pete Townshend: It is something I’d like to develop, but no, I’m not very good at it. I think maybe it’s because I’ve always felt that I’ve never developed it in The Who because I’ve never been a proper frontman. I’ve always been able to know that if I went on the stage with a scowl on my face, that it wouldn’t matter, there are three other people up there and they can grin.

Steve Harris: I’ve got a question about your approach to songwriting. I guess you still write story-oriented albums like “Iron Man” and “Psychoderelict.” Is that just an ability that you latched onto when you were young and you sort of stuck with?

Pete Townshend: I think it is something that I started, I did start to deal in story when I was young, but I’m not a very good storyteller in the traditional sense. I’m not very good at building characters and developing characters as a way of gathering, building an approach to an adventure or to some kind of cause. So what I actually find that I do is, is that I tend to write very much from inside and very unconsciously. If I write a story or if I’m trying to attend to a wider theme, what it does is it disables that somewhat, it makes me write it a little bit less-unconsciously. Hopefully it makes my writing a little bit more universal and that’s why I do it. I often find that with “Tommy,” for example, the trick doesn’t work because in the end, what actually happens is, is that I, you know, the years pass and I look at something like “Tommy” and I think, although I did write this story about this poor, deaf, dumb, and blind kid who wants to cross over back into normality as a, you know, allegory of the spiritual path, it turns out to be in a sense, subliminally, very autobiographical, so the trick doesn’t always work.

Steve Harris: I guess the funny thing about “Tommy” is that we think of it as a classic story, but nobody really remembers the story. They just think that it was great because it was a story. So I guess that in its own way, it does work as a device.

Pete Townshend: Well, you know, anything that gets you writing songs has gotta be good, it’s very hard to write songs. Anybody will tell you that. It gets harder and harder as time passes by, particularly to do things that are genuinely new. Not that newness in itself is important, but certainly, it’s part of the thing that nurtures the creative spirit is the idea that you are doing things which you haven’t done before. Hopefully, you’re doing things which nobody else has done before in quite the same way. They might have approached the same problems, but they won’t have done the same thing. So I actually sit down often to write. I end up playing the guitar or tinkling away at the piano or writing a few lines of verse. But I don’t end up with a song. Whereas if I actually have a story or a mission, a brief in front of me, it challenges me, it inspires me. And it also makes me forget myself. And I find it very helpful. And in fact, I don’t plan to make any more records. I just really want to write songs for theater.

Steve Harris: Well, wait a minute, maybe you could elaborate a little bit more on that. That’s sounds like a major decision on your part.

Pete Townshend: Well, you know, it’s not particularly major, you know? “Psychoderelict” only sold couple of 100,000 albums. My recording career is virtually over anyway. I’m not really interested in it. You know, “Tommy” on the other hand grossed, has so far grossed something like $135 million. I don’t have to fiddle around making albums because I happen to be seen to be a dinosaur rock star. I’m very, very interested in writing songs for music concept, I always have been. It’s not some, and music concept, it’s not something which is very highly regarded in pop. In fact, it’s considered pretentious, and people still sneer at it. I prefer to work in a medium where it is valued, which is, I suppose, in music theater, or indeed even in opera.

Steve Harris: When you say that music concept is sneered at, I don’t quite follow you.

Pete Townshend: I think the idea that if a songwriter put out a concept album, an album in which all the songs were linked in some way, that had some kind of sense of order, that there was a general continuum about which flowed through the material, and which the material attended to, that is considered a conceit in the pop industry, because in the pop industry, the idea is that, you know, which is something that I’ve very much ascribed to. I think it is a wonderful thing. The great thing about a great pop song is it’s like your daily bread, it gets you through the day. And I was once a very, very good baker of bread, but I can’t do it anymore, I just can’t be bothered. Other people can do it far better.

Steve Harris: How does this most recent compilation fit in with what you are and what you wanna do right now?

Pete Townshend: It’s the end of what I used to do. It’s come out, I did actually owe one more album to Atlantic and I was really wondering what the fucking hell I was gonna put out. And then luckily, they sacked Doug Morris, who was the guy that signed me. And I had a key man clause, meaning that when he left, I didn’t have to deliver the album. So I agreed to deliver this final collection, and to promote it with some small concerts and radio and TV, which I’ve done, and I must say, I very much enjoyed doing that. But my life plan is that I will not try to make pop records anymore. And then, I don’t have to make any more fucking videos.

Steve Harris: You say that with sort of resentment dripping from your lips.

Pete Townshend: Well, doesn’t everybody? I suppose there must be people that like being pushed around by people that make, most of the time make hairspray commercials, but I don’t.

Steve Harris: I see, so you really want out and you want out bad.

Pete Townshend: I am out, I’ve been out for ages, really.

Steve Harris: As we speak right now, you’re in the middle of a slew of interviews with the foreign press. Is that the phase you’re in right now?

Pete Townshend: No, no, I’m doing two interviews today with Japan. That’s all, and I think this is probably really in response to the fact that I told my record company that I’m very interested in dispelling the notion that I’ve received from a few Japanese journalists that I hate the Japanese. I’m very keen to dispel that because I think Japan is probably a very good place for me to start looking at developing this new craft. I do think that there’s something about the way that the Japanese respond to experimental work with great interest and capacity to concentrate that maybe would give some of the things that I’m planning a bit of a shot, bit more of a shot than they would get if they were chatted about on VH1, or “Entertainment Tonight,” or alternatively, they appeared at the Almeida Theatre, or the Royal Court, or the Young Vic, or some other arty-farty joint in London. So, but I have been very conscious lately of the fact that it seems to me to have been a great mistake that as for me, not so much as a member of The Who, but as a solo artist, to have never even visited Japan. But the world is so big, I mean, this is the thing that bothers me always. I find the world just too big. When I was in The Who, it was always the only way that we could meet the audience that we needed to meet was to play these huge fucking football stadiums and I hated it.

Steve Harris: The musical world, I mean, in terms of musical markets is not that big, and Japan figures very prominently economically in the musical world. How is it that you could have overlooked a market this big?

Pete Townshend: Well, I don’t think we’ve overlooked it. I think we’ve actually said that we couldn’t honor it. We couldn’t do it justice. There wasn’t enough time.

Steve Harris: Couldn’t you have snuck in two weeks in between stadium?

Pete Townshend: Would that I’ve been honoring it?

Steve Harris: I mean, nobody else really spends that much longer here because there aren’t that many places to play.

Pete Townshend: Well, you know, I don’t know. I mean, you know, as I said, I can see that it’s probably a mistake, but that’s what, that’s where I am today. And I certainly think that this is something that I need to put right. Although I’m attempting to put it right at a place where I’m actually making an enormous change in my life. I think one of the things, one of the reasons, the other reasons why I suppose, it’s interesting to look at what might happen for me as a writer, as a composer in Japan, is that I suppose you must know, is that, you know, “Quadrophenia,” for example, which is a piece that I’m very interested in trying to develop as a concert theater piece, has always had a very strong attraction in Japan, even though it’s quite parochial, you know, it’s very much an English idea. In the last five or six years, the whole idea, and particularly this year of all years, the idea of what mod came from, what the whole, what the expression of mod was all about. The idea that behind fashion, and behind the apparent mindless dressing up, and everybody looking the same, that behind that was some kind of spiritual search, some kind of spiritual yearning, which could only be expressed in congregation, seems to be something that Japanese people understand. So we might actually bring “Quadrophenia” to Japan. You know, I haven’t got any plans for that yet, but you know, when we finish, we’re doing it in Hyde Park on the 29th, and then we’re gonna take it to New York so that we can try doing it inside indoors. And then, I’d like to try and do it in a number of other places because I just think that it’s, I think it’s the best album that The Who made. But I also think it’s one of the most cohesive stories that I wrote, and in doing this kind of thing, I learn a tremendous amount. It seems to me to be a fairly safe entry into the Japanese performance area. But what I’d really like to do is I’d like to come over with my guitar and a suitcase, and play a few small concert halls.

Steve Harris: What kind of material would you be doing, would it just be a lot of selective material over the years, or…

Pete Townshend: Yes, well, I just did a small tour like that in the States. I played House of Blues, and the Fillmore, and the Supper Club in New York. And I really, really enjoyed it. I don’t think the audiences were much bigger than 1,000 people. And I played all kinds of strange things. I played songs from my career which are fairly rare, but I also played a couple of Mose Allison songs, and a thing by Charlie Mingus, and folk songs, and odd things like that. I mean, but basically what I was trying to do was trying to learn what it is that I still have as a performer, as a solo artist, it was like being reborn. It was very interesting. And I was genuinely happy on the stage, which is not something that I’ve ever been before, really. I’ve never really liked being on the stage very much.

Steve Harris: And that there was just you and your guitar, that’s all.

Pete Townshend: I had a guy with me, a guy called Jon Carin, who was a keyboard player that I met. He worked with Pink Floyd. And he played Kurzweil and sang, and he’s a quite a good guitar player as well. So what he was actually able to do is he was able to help me play a much wider variety of material than I otherwise could have done. I played piano quite a lot as well. I’m not very good at the piano, but it’s important that I play it on the stage because so many of the songs that I’ve written, I’ve written on the piano and they sound better when they’re played on the piano. Even if they’re played badly by me.

Steve Harris: This is a rather crass question, but as you’re talking about making a big break with your past while exploring these new artistic avenues, how exactly does this June 29th Prince Trust gig for The Who fit in? What exactly–

Pete Townshend: Well, firstly, you know, it’s only the press that are calling it a Who gig. It’s not a Who gig.

Steve Harris: Oh, okay.

Pete Townshend: It’s my show, I wrote a script of “Quadrophenia,” and early this year, I committed to do a solo show for the Prince’s Trust. I actually produced the first two concerts for the Prince’s Trust with George Martin in 81, 82 and 83. So I committed to do this concert. And then, about three months ago, Harvey Goldsmith told me that it was for 150,000 people. And I just freaked. I thought, well, what the fuck am I gonna do? Go out there with a guitar and, you know, and strum in front of 150,000 people. So at first I thought I might do “Psychoderelict,” that thing I did in 93. And then I realized that nobody would know what the fuck it was about. So I decided to do “Quadrophenia.” And I started to talk about it with various people and discovered that I wasn’t really gonna be able to afford to put it on without sponsorships. So we spoke to a few sponsors, and of course, the sponsors would only put the money up if they understood it as a Who gig. So I kept telling them, “No, this is not a Who gig. “This is ‘Quadrophenia,'” but in the end, I agreed to ask Roger whether he would sing on the thing ’cause I felt that, you know, anyway, he would certainly do a great job on it. And he agreed to sing on it. And we immediately got our sponsorship, which we needed to make the movie to show, to tell the story, which we got from MasterCard. And it kind of proceeded from there. The script that I’ve written is designed really, as a concert vehicle for celebrities, you know, Roger Daltrey is a celebrity. And he said that if he and I appeared on a concert and that we didn’t invite John Entwistle, so that John would be very upset. So I invited John and John said he was far too busy doing something else, but in the end, he changed his plans and he agreed to play. And there you have it, a Who gig. I’m only singing three or four songs, and I’m not playing guitar. So it’s not really a Who gig. And we won’t be playing anything, we won’t be playing any old Who songs. I mean, I’m not, you know, I’m not afraid of getting up on the stage and being seen to be The Who. I’m very proud of what The Who did. I’m very proud of my relationship and my friendship to the surviving members of The Who. It’s just that I don’t want to cheat people, you know?

Steve Harris: So who else is involved in this thing? Who will be actually there that night?

Pete Townshend: It’s not, unfortunately, it’s not night. It’s very close to the longest day of the year. So the whole thing will be done in daylight, which makes it quite complicated. It’s at a concert, Alanis Morissette is doing a show. Bob Dylan is doing a show. Then we’re doing “Quadrophenia.” And then, Eric Clapton is doing a show. In the “Quadrophenia” section, there’s a number of people in the movie, which you’ll see in the back projection, a number of surprise celebrities. And there are a number of surprise celebrities who will appear on the stage along with me and Roger.

Steve Harris: I see, but I guess half the show is just sort of springing the surprises for the people who happen to be there that day.

Pete Townshend: That’s right, I mean, I think a couple of names have started to leak out. A couple of the people that I asked to begin with agreed, and then pulled out. So I think it’s probably best not to mention any names. The other thing that my manager said is that I shouldn’t mention any names until he’s finalized the contracts for New York.

Steve Harris: I think we’ve covered all the avenues you’re pursuing at present, right? Because there were like about three matters concerning the past that this guy wants to clear up for some reason. Would it be okay to move on to that? You basically informed us of all that you’re doing now.

Pete Townshend: Well, I continue to be involved in the remastering of old Who product. I’m particularly proud of the remixing of “Quadrophenia,” which I think is partly why I wanted to accelerate this live performance aspect of it because the album was an album, you may or may not know, which I produced. Although I’m very proud of what I did, I took on more than I could handle. And towards the end, particularly in the mixing, I think I ill-served the record. And what’s happened is that when we’ve remixed it, it’s really turned out to be absolutely spectacular, well, in my view, just fabulous. And so I’m very proud of that work that I’ve been doing. And I’m also looking back to some extent, because I’m considering at the moment writing an autobiography, but you know, what I do at home every day that’s new is I sit down and I try and write new things. And I have a couple of hours a day, every day dedicated to writing. But unfortunately, until I do write something new, and it pays the rent, I’ll constantly be going back. Obviously, the other thing about going back is to honor what we’ve done in the past. And I have no difficulty with that whatsoever.

Steve Harris: When you sit down to do your couple of hours of writing new material, now, you’re still using that device where you have like a big picture and you sort of fill in the pieces then?

Pete Townshend: That’s right, I’m at the moment, I’m writing fairly modest, what I’d call chamber plays. I’ve, chamber music, so I’ve written a story called “Stella,” which is really quite short, about a playwright and an actress. And another story called “Toby’s Piano,” which is about a woman who encourages a young man to play the piano. And these two stories are fairly modest, but they are producing songs. They inspire me to write songs. And I might put those plays together and try and put them on together somewhere. Or I might just have to bury them if they don’t work properly. But that’s the kind of thing I’m doing.

Steve Harris: So you always have theater in mind, you never have cinema in mind?

Pete Townshend: I’m not a fan of movies, I’m afraid. I like film, but I don’t, you know, I think the composer’s art is a higher art than the film director’s art.

Steve Harris: A higher art meaning?

Pete Townshend: It’s a higher art. I mean, it’s, you know, we work in a much higher place. We are superior beings.

Steve Harris: All right, why didn’t you say so? Okay.

Pete Townshend: And when you are a composer and you work in movies, you have to be subordinate to the director, which is fair enough because that’s their genre. I find it very difficult because, I don’t know, just to give you an example. You know, a film composer might say to me, “I would like to work with you on my movie.” And I would say, “Well, why?” And they would say, “Well, because your music is so kind of filmic.” And I would say, “Well, can you explain to me “what you mean by that?” And they would say, “Well, it creates images in my head.” And I would say, “Well good, so the job is done then.” Because the next step of course, is for the film director to try to get me to write more music, which will help to create the images in the audience’s head that he wants to make. Well, that’s his job. And in actual fact, there are composers that are brilliant at doing that. I’m not very good it unfortunately.

Steve Harris: Are you also an avid theater goer?

Pete Townshend: These days, yes, I don’t enjoy very much of music theater. The last thing that I saw that I suppose I should have enjoyed as much as everybody else was I saw “Rent” in New York and although it purports to be a rock musical and it does have some fantastic moments, I think it’s a pity that it wasn’t completely finished before the writer died. But I do think that’s the way I want to go. I want to go, I love the whole process of theater. I like the, you know, I hope it’s not a full theater. But financially, it doesn’t seem to be a form that is dying at all, so. But “Iron Man,” for example, it’s being turned into a feature-length animation film by Warner Brothers, and the way that modern feature-length animation films are being made is they’re being made like Hollywood musicals of the 50s. And that’s the only place where they can use those techniques, you know? It’s like you couldn’t make “Singing in the Rain” today, but you could if you turned it into a cartoon.

Steve Harris: Huh, maybe you could simplify that for me. What connects those two art forms? What connects musicals from the 50s and animation now?

Pete Townshend: Well, the new genre feature-length animated films, the new batch of them from, I suppose, “Little Mermaid” onwards were conceived in Disney, by Howard Ashman and Alan Menken, who were two Broadway theater writers. And they produced “Little Mermaid, “Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin,” and started on “Lion King.” And I suppose “Pocahontas” is one of the same kind of thing. So what they’re actually doing is they’re using the laws and rules of musical comedy in order to create story and dynamic for animation. In other words, the characters keep bursting into song. And you can’t do that in movies anymore.

Steve Harris: Yeah, that’s right, that’s right.

Pete Townshend: But you can in cartoons, so I am very interested in that. In fact, a lot of people, like Elton John for example, is working in that area.

Steve Harris: Right, right, right.

Pete Townshend: With Tim Ross, they’ve just done “Aida.”

Steve Harris: Do you feel comfortable watching like an hour and 45 minutes of cartoons though?

Pete Townshend: Do I feel comfortable watching it?

Steve Harris: Yeah.

Pete Townshend: I don’t have to watch it. I just have to write it.

Steve Harris: Okay.

Steve Harris: Okay, but as an aesthetic statement, it’s not exactly your cup of tea, then?

Pete Townshend: Well, it’s difficult, isn’t it? Because I grew up with this stuff, like so many people did. I’m not sure that I’m entirely clear about what my aesthetic statement is or needs to be. I think that’s one of the things that perhaps I have to look at on a regular basis is, you know, when I start to write something is to ask myself, why am I writing this? What is it that I want to say? This is not a question that I asked myself very often when I was writing for The Who, or indeed, as a solo artist. I just thought, well, I’ll write a bunch of songs, and chuck ’em out and see what happens. These days, I think what’s really important for me, it’s not just that I’m writing something and I understand what it is that I’m writing or why I’m writing it, but it’s more important that I enjoy the process rather than the end result. So when you asked me the question, do I enjoy sitting through 90 minutes of animated musical feature, my response is that I don’t think that it matters. I think what matters is that if I work on a 90-minute musical feature, I should enjoy it. I should be happy while I’m doing it because, “Iron Man” for example, it’s gonna be four years of work. I must enjoy the process. I mustn’t do what I did in The Who, which is to be out on the road with them for 10 years and hate every fucking minute of it.

Steve Harris: What about one of the more famous examples, the movie “Quadrophenia,” what did you think of the end product?

Pete Townshend: Well, I didn’t have very much to do with that, but I think it’s a good film. It’s a capable, British, what we call a good little film in the UK.

Steve Harris: Just moving back a couple of paragraphs here, maybe you could explain in a little more detail, what exactly goes into the remixing process? You said that the remixing of “Quadrophenia,” for example, has improved it immensely. How is it different now than it was then? What sort of different decisions are you making now in that actual process?

Pete Townshend: Well, in actual fact, We’re not making any different decisions. We’re copying what I did, but we’re working with better monitor speakers, better mastering techniques at the end. In other words, you know, the original multi-track tapes, which were recorded by The Who in the studio sounded pretty good when we played them back. What didn’t sound pretty good were the mixes, you know, the actual end result, the CDs, the vinyl albums, the things that the public bought didn’t sound as good as what we heard in the studio.

Steve Harris: Oh, okay.

Pete Townshend: What you can do today is you can really greatly approach what people heard in the studio, because the final chain is much purer. I remember when I mastered “Quadrophenia” in Los Angeles, MCA Records, who were releasing it there, asked for a number of copies of the copy masters to send out to duplicating plants to make cassettes. And I worked it out that some of the commercial cassettes that people were then buying because CDs hadn’t been invented then we’re up to eight generations old. They were copies, of copies, of copies, of copies, of copies, of copies, of copies, of copies, of copies, of copies, and as such, they were pretty crappy. And the mastering that we were doing in LA was not good enough, not, sorry, it was not gonna serve Japan, or Germany, or South America, or Australia, that what we had to send to those countries were copy tapes from which they would then make their own master copies. And what they would often do is when they received their copy masters is they would regard that copy master as their sacred master and make a copy of it, from which they would master the albums. But, you know, the main thing was, is that I think I fucked the thing up in the studio. I was just exhausted.

Steve Harris: So we’re just hearing a clearer version now. That’s basically the only difference.

Pete Townshend: I think, yeah, a much clearer… And it’s very important, because what somehow happened on the original was that the vocal performance got lost somehow. Maybe there was some kind of phase problem, I don’t know.

Steve Harris: How about the Isle of Wight Festival video that I think that will be coming out soon, why is that coming out now? And is that a particularly live performance you’re particularly proud of?

Pete Townshend: It’s all right. I don’t have any strong views about it, particularly. I mean, I think it’s coming out because we just found it.

Steve Harris: Ah, where was it?

Pete Townshend: It was in my, it was in my warehouse, but you know, we also found a Jimmy Hendrix marked up as The Who.

Steve Harris: Yet another Jimi Hendrix tape emerges, right?

Pete Townshend: Yeah, although the movie of Jimmy Hendrix and the soundtrack in mono has already been released. We found the eight-track masters and they’ve been mislabeled as The Who. So when I found The Who’s tapes, we also found the Jimmy Hendrix one, so that was nice. And a few other people too, Joni Mitchell and couple of other the acts on the Isle of Wight Festival. The Who’s performance is pretty good, I think. It’s one of the best at the time.

Steve Harris: Are there a lot of these goodies kicking around in warehouses?

Pete Townshend: We only had one warehouse, and it’s not very big, and it’s next to my house. And we think we’d cataloged everything very, very carefully, but you know, with a lot of things, we can’t, we trust that what is in the box is what is in the box. And in this case it was just wrong. It wasn’t only that it was labeled wrongly. It wasn’t labeled as The Isle of Wight, so we found it by accident. We were looking for something else.

Steve Harris: “Lifehouse,” did that project ever come to fruition?

Pete Townshend: Well, if it had a done, I’m sure you would have known about it. No, I just had a script meeting with somebody, I’m fiddling around, I’m fiddling around with it all the time. I can’t let it go. I’m really enamored with it, I’m finding it very difficult to make it work.

Steve Harris: It’s something that you couldn’t make work with The Who, right?

Pete Townshend: I couldn’t make it work with The Who simply because I was being far too ambitious, but what I’m finding now is just that I’m finding it difficult to make it work because I think times have changed. Some of the ideas which were very far-reaching, and quite sort of smart back in 1971, are now a wee bit passe, but you know, the general idea is one which I still feel passionate about.

Steve Harris: What do you think it’s gonna take to bring this thing to fruition?

Pete Townshend: You know, I think I have to sit down and fucking write the thing properly. You know, I’m working with another writer and we just, I mean, what actually happened in this conference was just that I realized that, you know, that I hadn’t explained a number of very important points to this guy clearly enough, and you know, that we were not collaborating really honestly. And I think that, you know, I’ve been working on my own for far too long, and I’m still learning about the art of collaboration. I’m not good at it yet. And I need to be because you can’t work in theater, or in film, or in any of these mediums as a writer unless you can collaborate. I think I’m okay at being part of a team, but I find it very hard to sit down and write with somebody else. It seems, oh god, I dunno how it seems, it’s strange. I’ve never done it before. I mean, the only time I’ve come close to it is as an editor.

Steve Harris: There are questions here about why you’ve always been revered by youth on the cutting edge, as it were, you know, when you were mods, when even when punk was all the rage back in 77, 78, that there always seemed to be a lot of affection and appreciation for The Who. Is there a universality to what you’ve been doing?

Pete Townshend: I dunno, is that for me to say, I don’t really know. I mean, I’ve never, never really quite, I’ve always been very grateful, but I’ve just always analyzed it that, you know, that we were with a number of other bands in the 60s, were kind of first on our block to steal R and B and turn it into pink music, I dunno.

Steve Harris: Okay. Couldn’t think of a pithy comment for that one, eh? Good enough and they ask you to look back on the day of the mods 30 years later, you talked about it a little while ago, and what it might mean to the Japanese. Looking back in retrospect, what does it mean to you?

Pete Townshend: Well, I remember it as being just not what I expected. I’d already, when I was about 17, 18, 19, that kind of age, I’d already found myself as part of a new fellowship, which I discovered at art school. I went to art school when I was 16 and what I found were people that liked to talk, and liked to exchange ideas, and liked discussing the creative process, and liked to work with abstract ideas. And I suppose they liked being pretentious. I don’t know, but, you know, whatever it was, I felt comfortable there. And as part of that, at that time, which is 1961, I heard a lot of jazz, and R&B, a lot of Black music that I hadn’t heard before for the first time. But I also heard a lot of American music that I hadn’t heard before. Like I hadn’t heard any of the political minstrels. I hadn’t heard, well, I’d heard them, but I didn’t know what they were. I didn’t know about Joan Baez, or Bob Dylan, or Pete Seeger, or any of those guys. And it was a huge kind of a huge thing for me to go through. But at the same time, I felt like a bit of an impostor because I was after all, a kid from West London. Obviously, a lot of these people were kids from West London, but, you know, I was a kid from West London. I didn’t feel entirely comfortable. So when The Who started to do shows and we started to find this audience, who had at the same time, also discovered Black music. These were people that hadn’t been to our college. These were people that were clerks in banks, and kids that worked in advertising agencies, and dustmen, and postmen, and bus drivers, and people like that who had also discovered New Orleans dance music, and Tamla-Motown, and stuff like that through being exposed to it in London dancing clubs. I dunno, it kind of, it drew some strings together. It made me feel that the inner recognition of the music that I had tied in with something about who I was, and where I’d grown up, and what the mod movement did, is it tied that up under a philosophical, under a philosophical banner. And I suppose the philosophy in a nutshell was that you can be ordinary, but you can also be special, even with very limited resources. Even if you’re a very simple soul. You could simply decide that you are gonna be a nice face. You can simply decide that you’re gonna be cool, and you can be cool. And I think that that also was something that was borrowed from Black behavior, particularly in the UK, from observing Caribbeans. And I think all this hit me like a flash when The Who were playing at the Aquarium Ballroom in Brighton in 1964. I was 19 years old, you know, I was still going to art school even though The Who were performing. We were called the High Numbers then. I was still going to art school every now and again, because I didn’t want to lose my grant. And suddenly, there I was on the beachfront wearing my, what to me, was stage clothes, you know, my mod outfit, with a bunch of mod kids. And you may have read about this particular moment, heard about this moment that I’ve spoken about a couple of times before. I just felt, I dunno, I felt kind of, I felt bigger because I was less me and more one of the crowd. I felt that I found myself through losing myself. I know it sounds incredibly pompous, but that’s what I felt.

Steve Harris: Maybe that’s the universality of Pete Townshend and The Who, I mean, because it seems like when you look at youth movements, isn’t that always the objective, and isn’t that always the ultimate gratification when you are able to find a place for yourself?

Pete Townshend: I think it is. I think what older people will do is they’ll look at it knowingly and with a certain amount of sanguinity and say, “Well, hold on a minute, “don’t they realize that that’s what art is?” Or go even further and say, “Don’t they realize that’s what family is,” or “that’s what society is,” or “that’s what life is?” But you have to be led into these wisdoms. And although R&B and jazz were very important to me as a young man, the mod movement was what, in the UK, being with a bunch of working class blokes down in Brighton was what really made it all seem right to me. Now I believe that it led me to a great understanding of the importance of congregation, congregation of like-minded spirits, whether it’s a football match, or a concert, or even even a techno rave joint. People lose themselves by being together. And I think it’s, and it’s as close as a lot of us get to a genuine spiritual moment in our lives.

Steve Harris: I guess it’s also very important at the same time that the people get to see that they carved it out of nothing, that they made it happen, that they sort of willed it to happen.

Pete Townshend: More that it was inspired by a like-minded group of people. I know from West London mods that, you know, I used to think, God, this is so hypocritical. Here we are kind of playing Black music, but, you know, we haven’t suffered like they’ve suffered. We’ve never been slaves. And I remember a few kids used to turn on me and say, you know, angrily, “Well, Pete, “you may not have been a fucking slave, but I’m a slave. “You should try coming and doing the job I do.”

Steve Harris: That’s right, that’s right. There are people out there really singing the blues.

Pete Townshend: Yeah,

Steve Harris: That’s right, okay. That’s great, but there’s one last question here. And I hate this question because it is so glib, but I will ask it anyway, because that’s what they’re paying me to do. And it’s about the “hope I die before I get old” line from “My Generation” which this guy thinks maybe inspired a lot of people to kind of go off the deep end while they were still young. In spite of the fact that many people did go off the deep end when they were young, you survived and you thrived, and does that make you feel different now than you did then?

Pete Townshend: What if it was, if it, I dunno, if it was a recommendation of teenage suicide, then obviously, I’m not very comfortable about it, but I don’t think that’s what it was. It was certainly never meant that way. And I think the reason that I’ve survived is because I’ve had people in my life that cared about me. And I think that what I was writing about when I was young, was that feeling of not being cared for, but being discarded in a sense by society, being undervalued by the establishment. And it seemed to me to be a type of thinking and an attitude that when I was 19 years old and I wrote the song, I used to think, well, only old people think that way, and I never wanna be like them. But in a sense, it was actually, rather than a recommendation to suicide, it was an affirmation of life, I think.

Steve Harris: I see, so you were sort of speaking out for yourself, it was your own personal backlash.

Pete Townshend: Well, you know, I don’t, the other thing is, is that I have to remember that, you know, it wasn’t really personal, you know? “My Generation” was a very, very skillful bit of songwriting. It’s got a bit of Bob Dylan in there. It’s got a bit of Mose Allison in there. There’s a bit of the Beach Boys in there. There’s a bit of Johnny Cash, a bit of Bo Diddley. There’s a bit of “Louie, Louie.” There’s all kinds of stuff in there because what I needed at the time was a composite that would not only hit the marketplace, but would also allow the band to identify. You know, unless I’d had that line, “People try to put us down just because we get around,” Keith Moon wouldn’t have played on it. It had to have a kind of Beach Boys flash. It had to have something in it that would make him feel that his obsession with the Beach Boys had a part in The Who’s process. So on the line, “I hope I die before I get old” was not something that I wrote for me or about me. It was something that I actually wrote for Roger. It was something that I felt that I wouldn’t have the courage to sing, but I felt that he was, if not man enough to sing it, certainly macho enough to sing it. A kind of an expression of a type of nihilism that I felt that he would feel comfortable expressing, ’cause we’d co-written “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere” together. A couple of the lines that he contributed to seemed to me, very nihilistic, it was almost like he, he kept talking about locked door and I can smash through lock doors. Do you know what I mean? That kind of thing. And “My Generation” was written actually around the time that I wrote “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere.” I wrote it quite a long time before it was recorded. I’m not pretending to be like the playwright here, and this is not my words, because obviously they, it did come from me, but I’ve never felt entirely comfortable about owning them. And what I’m trying to do today is, I suppose I am trying to own them. They are, it is a sentiment that I feel very passionately about. I still feel that I hope I die before I get old. I hope, in a sense, there’s a spiritual subtext to the whole thing. It is that, that this life is fucking endless. Hell is doing the same thing over, and over, and over, and over, and over again, until you turn to dust. The way to reverse that process is to go back to the source, to defy atrophy, to allow your consciousness to grow, to attend to your spiritual life and your spiritual pathway, and the age old, old is what the universe is. Young is what the heart is and the soul is. So in a sense, if I can own it in that way, then maybe I’ll feel more comfortable about it. But I certainly, I don’t like the idea that a Kurt Cobain blows his brains out because he thinks that he’s had instructions from Pete Townshend, pop guru. I think what that was about was, is that there was nobody there that knew how to stop him. It wasn’t that nobody cared, but you know, if there’s a tragedy at work there, it is that this business of ours, this rock and roll industry is too young, to ill-equipped, to young, to new to have built up ways of helping people that have got a problem. We don’t know how to do it. There are too many kind of, and one could be cynical, and say that, you know, “The poor fucker was worth more dead than alive.” It’s not true, of course it’s not true. It’s just not true. The temptation to think that somehow, that James Dean is worth more dead than alive, that Jimi Hendrix is worth more dead than alive, you know? And in the case of people like Brian Jones, Janis Joplin, and particularly Brian Jones and Jimmy Hendrix, these were people that were my friends. These are not fucking marquee names. These are not icons. These are not people that you wear on tee shirts. These were people that I knew, people that I cared about, you know, people that were like me. They were in show business, they were frail, they were vulnerable, they put themselves on the line, and then suddenly, they’re dead. And because they’re dead, somehow everything that they are is exaggerated, is much bigger. The bad things that they do are suddenly turned into good things. And the good things that they do have somehow, therefore, exalted into acts of cosmic genius that are out of all proportion with reality. You know, Jimi Hendrix’s great, great talents were almost unscratched at when he died.

Steve Harris: Isn’t that what history does to just about everybody though? It’s not just icons.

Pete Townshend: I think it does. I suppose what I’m doing isn’t getting angry about the idea that, oh, I don’t know. I met Jimi in LA a couple of weeks before he died and I actually thought he looked happier than I’d ever seen him, you know, I just, it never occurred to me that he was probably on some unbelievable kind of tranquilizer, but do you know what I mean? I always think that there should be somebody there to catch them when they fall. But then, you know, that idea is completely blown out of the sky by Brian Wilson and Elvis Presley, both had resident doctors who did fucking nothing but harm.

Steve Harris: That’s right, that’s right, that’s right. The saving of people, it’s a very difficult task. I think I’ve got basically everything they asked me to get.

Pete Townshend: Right.

Steve Harris: So yeah, I thank you very much for your time and your eloquence. And I certainly hope that Japan does become your test ground for “Quadrophenia.”

Pete Townshend: Yeah, yeah. I think it’s a good notion. I think what I really ought to do is jump on a plane and come and have a look first. I’ve always said that I would never, the first time I went to Japan, I would go as a tourist. And I think that that would be a good thing to do. Just get walk around.

Steve Harris: I think if nothing else, you’ll first of all sense that there’s none of this sort of cynicism that could sink that sort of project before it gets off the ground. So if for no other reason, I would come here just to sort of feel the positive vibe and the energy and all of that.

Pete Townshend: Well, that sounds good. All right, well, listen, thanks a lot, Steve.

Steve Harris: Yeah, okay, well, it’s been a pleasure, and I hope to talk to you again sometime.

Pete Townshend: Okay, I hope we meet one day.

Steve Harris: Okay, thank you very much.

Pete Townshend: All right, bye.

Steve Harris: Okay, bye-bye.